Mutanjan Recipe: Ornate Sweet Rice from the Mughal Kitchen

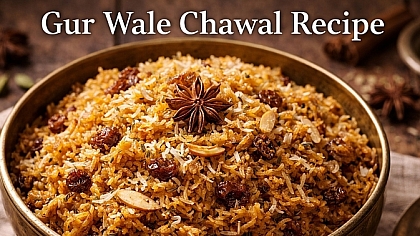

Mutanjan is not a subtle dish, nor is it meant to be. This jewel-toned sweet rice is a celebration of abundance — fragrant basmati grains coated in sugar and butter, studded with dried fruits, coconut, and candied cherries, and delicately perfumed with cardamom. Historically associated with royal kitchens and ceremonial feasts, mutanjan was prepared to signal generosity, festivity, and refinement.

Unlike simpler jaggery-based sweet rice, mutanjan relies on white sugar for clarity of colour and a clean sweetness. The visual appeal is central to its identity: pastel hues, glossy grains, and a generous scattering of fruit. Yet beneath the ornamentation lies careful technique — rice cooked just shy of done, then finished slowly so it absorbs flavour without losing structure.

Ingredients

- 1 cup basmati rice (pre-soaked)

- 1 cup sugar

- 50 g butter or ghee

- 3 green cardamom pods (elaichi), lightly crushed

- 2–3 drops neutral oil, such as sunflower (to prevent the butter from burning)

- 2–3 tablespoons sultanas

- 2–3 tablespoons coconut flakes

- 2–3 tablespoons glacé cherries, halved

- Food colouring (traditionally, pastel shades), as needed

Method

-

Cook the rice: The rice should be rinsed until the water runs clear and pre-soaked. Cook it in 1 cup of water until the water is fully absorbed and the rice is about 80 per cent cooked. The grains should be separate and firm. Remove from heat and set aside.

-

Prepare the syrup base: In a heavy-bottomed pan, melt the butter (or ghee) with a few drops of oil over low heat. Add the sugar and crushed cardamom pods and 1/2 cup of water, stirring gently until the sugar dissolves and forms a smooth, glossy syrup. Do not allow it to caramelise.

-

Assemble the mutanjan: Add the partially cooked rice to the syrup, folding gently to coat each grain. Stir in the sultanas, coconut flakes, and glacé cherries. Add a small amount of food colouring, distributing it lightly rather than fully blending for a marbled effect.

-

Finish cooking: Cover the pan and cook on very low heat until the rice is fully tender and infused with sweetness. Avoid stirring frequently, as this can break the grains.

-

Rest and mix: Once cooked, remove from heat and allow the mutanjan to rest for a few minutes. Gently mix just before serving to distribute the fruits and colour evenly.

A Dish of Ceremony and Craft

Mutanjan is less about restraint and more about spectacle, yet it demands discipline in execution. Too much heat, and the sugar darkens; too much stirring, and the rice loses its elegance. When done well, each grain remains intact, glossy, and perfumed — sweet without heaviness, rich without excess.

Served warm or at room temperature, mutanjan remains a reminder of a culinary tradition where food was as much about visual poetry as it was about flavour. It is a dish meant for occasions, for shared tables, and for moments that call for something unmistakably special.