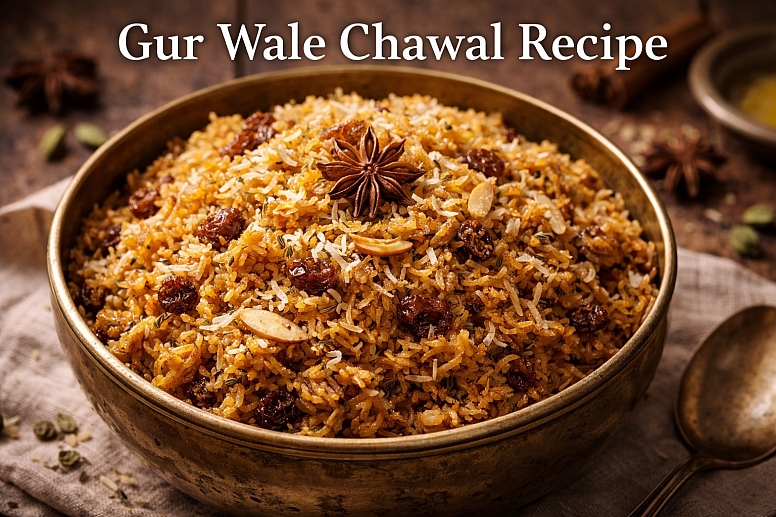

Gur Wale Chawal Recipe: Sweet Rice Cooked with Jaggery & Warm Spices

Few dishes capture the essence of North Indian home cooking quite like gur wale chawal. At first glance, it is disarmingly simple: rice cooked with jaggery, enriched with butter or ghee, and gently perfumed with spices. Yet this restraint is precisely what gives the dish its quiet power. Gur wale chawal is not about excess or ornamentation; it is about balance, timing, and an intuitive understanding of flavour.

Traditionally prepared in colder months, this sweet rice reflects a seasonal logic deeply embedded in everyday cooking. Jaggery replaces refined sugar, offering a mellow, caramel-like sweetness along with warmth and depth. Fennel seeds, cardamom, and star anise lend fragrance without overwhelming the dish, while coconut flakes and raisins add texture and contrast. The result sits comfortably between a dessert and a celebratory main — nourishing, comforting, and satisfying without being heavy.

The Role of Jaggery

Jaggery (gur) is central to this dish, both in flavour and philosophy. Less sharp than sugar and far more complex, it carries notes of molasses, smoke, and earth. When melted and folded into partially cooked rice, it coats each grain evenly, creating a glossy finish and a rounded sweetness that never feels cloying. The choice to match the jaggery to the weight of the rice reflects a home-cook’s instinct rather than a rigid formula — sweetness adjusted not by measurement alone, but by feel.

Technique Over Complexity

What makes Gur Wale Chawal special is not elaborate preparation but careful sequencing. Cooking the rice only to 80 per cent ensures that it absorbs the jaggery and milk without breaking. Toasting fennel seeds in ghee releases their essential oils, building aroma at the very foundation of the dish. A brief burst of high heat drives off excess moisture, while gentle steaming at the end allows the flavours to settle and harmonise.

Milk is used sparingly, not to make the dish creamy, but to soften the jaggery and bind the components together. Each step is deliberate, economical, and rooted in experience.

A Dish That Endures

Gur wale chawal endures because it answers a very human need: warmth, sweetness, and reassurance. It is food made without haste, meant to be eaten slowly. Whether served on its own or as part of a larger meal, it carries with it the quiet confidence of a recipe that has been cooked countless times, adjusted by hand and memory rather than instruction alone.

In an age of reinvention and embellishment, gur wale chawal remains unchanged — a reminder that some of the most enduring dishes are those that trust good ingredients, patient cooking, and the wisdom of tradition.

Unlike sugar-based sweets, jaggery lends a mellow, caramel-like sweetness and a depth of flavour that pairs beautifully with whole spices and ghee. The result is a dish that feels indulgent yet grounded in everyday kitchen wisdom.

Ingredients

- 1 cup pre-soaked basmati rice

- Jaggery (gur), equal in weight to the rice (approximately 1 cup, in small pieces so its easy to melt)

- 50 g butter or ghee

- ½ cup milk

- 3 green cardamom pods, lightly crushed

- 1 star anise

- 1 tablespoon fennel seeds (saunf)

- 2–3 tablespoons coconut flakes

- 2–3 tablespoons raisins

- 2–3 drops neutral oil (to prevent butter from burning)

Method

-

Cook the rice: The rice should be rinsed until the water runs clear and pre-soaked. Cook it with the cardamom pods and star anise in 1 cup of water until it is about 80% done. The grains should still have a slight bite, and the water should have absorbed, then set aside.

-

Prepare the jaggery: Gently melt the jaggery over low heat, stirring as needed, until smooth. Strain if necessary to remove impurities. Keep warm.

-

Build the base: In a heavy-bottomed pan, melt the butter (or ghee) with a few drops of oil. Add the fennel seeds and let them crackle. Stir in the coconut flakes and raisins, cooking until aromatic and lightly golden.

-

Combine: Add the partially cooked rice to the pan, followed by the melted jaggery and milk. Mix gently to avoid breaking the rice grains.

-

Finish cooking: Cook on a high flame for a few minutes to evaporate excess moisture, then reduce to low heat. Cover and let the rice steam until fully cooked and glossy, with each grain well coated in jaggery.

-

Rest and serve: Allow the dish to rest for 5–10 minutes before serving. Serve warm, on its own or as part of a festive spread.

A Dish Rooted in Tradition

Gur wale chawal is more than a recipe — it’s a seasonal ritual. The use of jaggery, fennel, and warming spices reflects an instinctive understanding of balance, especially during colder months. Simple in technique yet rich in flavour, it’s a reminder that some of the most enduring dishes come from restraint, patience, and good ingredients.